How did Emily Dickinson cope with aging?

Where I take a reader question and scour the Dickinson archives for an answer…

This question for Emily comes to us from reader Leigh Stein. If you’re not already familiar with Leigh Stein’s Attention Economy, please do check it out. I can’t speak highly enough about her insights and generosity! Leigh writes smart, funny, and generous posts about how to authentically find and connect with your audience.

I am 48 years old. But I don’t feel 48. Even though I look 48, even though peri-menopause is throwing me for a loop, even though I definitely experience that middle-aged-you-don’t-exist energy out in public, I still don’t feel that I’ve been around long enough to be 48. 37 sounds about right. Old enough to know a thing or two, but not old enough to be old.

We all have our particular brand of denial. The stakes are high, after all. Health problems emerge. Studies show that women in particular have a tougher time getting hired as they age. Peak unhappiness hits in the late 40s.

So, how did Emily Dickinson cope with aging? She wrote about it.

A year into the Civil War, at the age of 32, Emily wrote this:

This poem is perhaps more about time than aging. But aren’t the two concepts are inextricably linked? I think Dickinson is saying that the present is elusive, slippery, precious. The past and the future will forever try to seduce us, call to us across time, demand our psychic energy: rehash the past, dwell in regret and nostalgia; or, anticipate the future, wring our hands over the unknown of tomorrow. Time is a wave, forever curling over on itself. Get inside the barrel.

“We turn not older with years, but newer every day.”2

Emily was 42 when she wrote those words in a letter to her cousins, Louise and Frances Norcross, in 1872. She had already experienced extended challenges with her own health (her eyes) in addition to caring for a sick mother. Despite these setbacks, she viewed aging as a chance not to lose, but to gain, refresh, transform. To shed old skin and reveal new, tender cells beneath (I think Emily would have passed on the retinol). “We turn not older with years, but newer every day”: a useful turn of phrase if I’m ever passed over for a promotion for being too old.

At the age of 51, Emily’s tone shifts. A sense of longing and loss emerges.

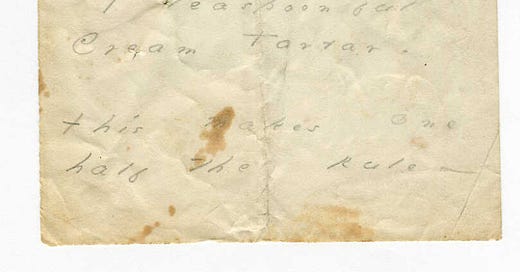

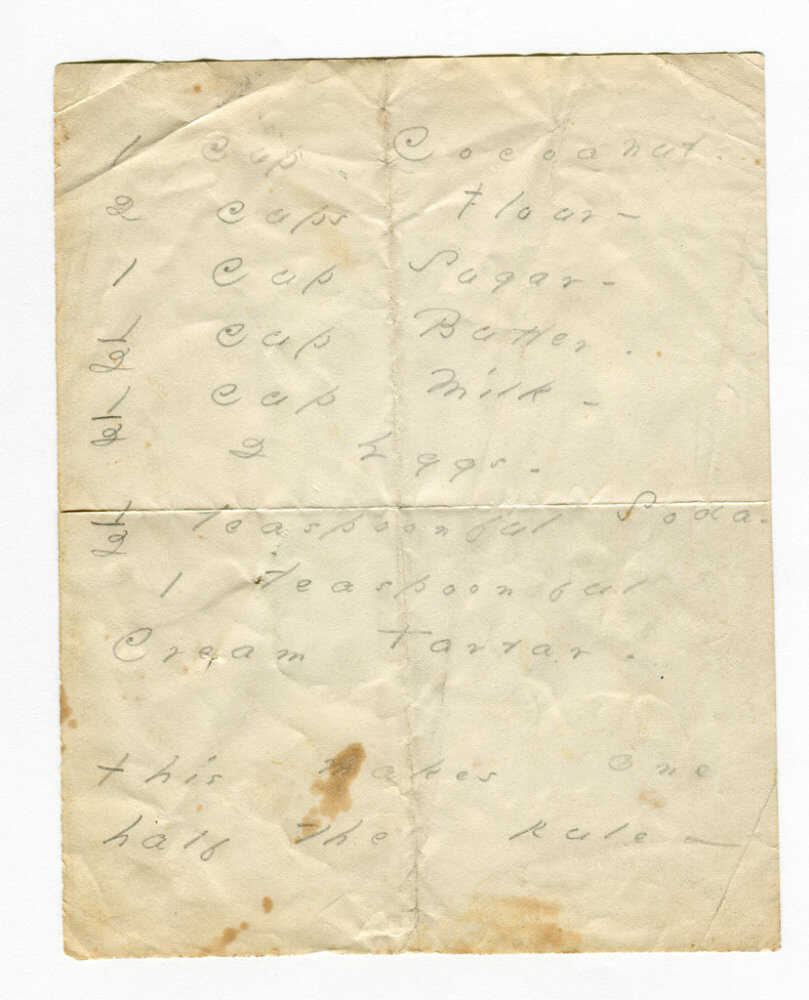

Emily wrote these lines (and the whole poem) on the back of a recipe for coconut cake in 1881, which she sent to her friend Elizabeth Holland. (Imagine getting a letter like that?)

Her missive on aging seems clear. Don’t waste energy staving off the inevitable or yearning for something long gone. As we might expect, the mighty Emily Dickinson sounds wise on the topic of aging.

And yet, there’s what Emily wrote, and then there’s what Emily did.

While some are eager to banish the idea of Emily Dickinson as the zany recluse and recast her as more of a heartthrob (such as Dickinson on Apple TV+), there is little debate about that fact that she retreated from the material world in her later years. She continued to write letters and poems to the end (though she slowed way down on the latter, which I wrote about in an earlier post on hot streaks), but she did not leave her father’s house to travel, visit, or entertain4. She often spoke to her guests from behind the closed door of her bedroom. It makes me wonder if, despite her rallying cries to cherish the present, aging hit Emily hard. If the vicissitudes of life wore her down; if disappointment ravaged her heart; if she nursed regret like other mortal souls. If she coped with aging by shutting out the noise.

In 1883, about three years before she died, she wrote another letter to her friend Elizabeth Holland. In it, she described the sorrow at the death of her young nephew, Gib:

“The Crisis of the sorrow of so many years is all that tires me”.5

Aging—the accumulation of Nows—need not be feared. But the accompanying loss, that is another story.

Finally, one more slanted truth from 1862, during Emily’s most prolific period of writing.

Copyright Credit: THE POEMS OF EMILY DICKINSON: READING EDITION, edited by Ralph W. Franklin, Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright © 1998, 1999 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright © 1951, 1955 , by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright © 1979, 1983 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright © 1914, 1918, 1924, 1929, 1930, 1932, 1935, 1937, 1942 by Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Copyright © 1952, 1957, 1958, 1963, 1965 by Mary L. Hampson.

Source: The Poems of Emily Dickinson Edited by R. W. Franklin (Harvard University Press, 1999)

Letter 379 to Louise and Frances Norcross, her cousins, 1872.

Smith, Martha Nell. “letters from Dickinson to Frances and Louise Norcross”. Dickinson Electronic Archives. Online. Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (IATH), University of Virginia. Available: https://archive.emilydickinson.org/correspondence/norcross/l379.html

Smith, Martha Nell. “Poems sent from Dickinson to Elizabeth Holland”. Dickinson Electronic Archives. Online. Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (IATH), University of Virginia. Available: https://archive.emilydickinson.org/correspondence/holland/p1515.html